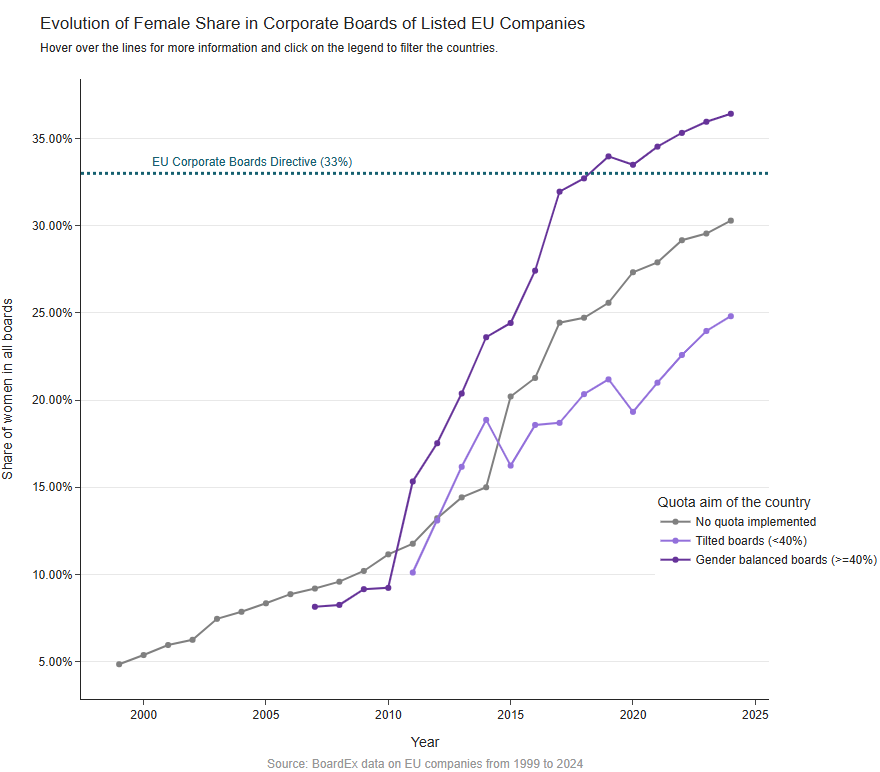

The European Parliament in 2022 enacted the Gender Balance on Corporate Boards Directive, a measure that stated that, by June 2026, large listed companies must achieve at least 40% representation of the underrepresented gender on supervisory boards and 33% among all directors. Our analysis of European listed companies using 2024 BoardEx data reveals a stark reality—only countries that already implemented the most progressive gender quotas are currently meeting these requirements.

Research consistently shows that quota design matters more than quotas themselves. Countries with strict enforcement mechanisms and supportive institutional frameworks achieve better results in board gender representation than those with weaker measures (Mensi-Klarbach & Seierstad, 2020).The Gender Balance on Corporate Boards Directive (2022/2381) established these binding targets with a June 30, 2026 deadline. However, the directive leaves enforcement mechanisms to individual member states, creating potential inconsistencies in implementation across the EU.

To assess current compliance levels, we analyzed member states by their existing gender quota policies. Our analysis uses a broader sample than the directive’s scope—we examined all listed companies in BoardEx’s 2024 database regardless of size, while the EU directive only applies to large companies meeting specific employee and asset thresholds. This means our findings include smaller listed companies that may not be subject to the directive’s requirements.

More details are included in the Data and Methods section at the end.

We categorized countries by their quota targets. Following Kirsch (2021), quotas below 40% represent “tilted measures”—initial steps toward gender parity—while targets of 40% or higher indicate genuine gender balance. Given that the directive establishes targets but not enforcement mechanisms, examining compliance based on existing national measures provides valuable insights into likely implementation success.

Interactive version available here

Our findings reveal a clear pattern: companies in countries with the most ambitious quota targets (40% or more) already exceed the EU directive’s requirements, averaging above the 33% threshold. Conversely, countries with moderate quotas (39% or less) perform worse than expected, while countries without formal quotas show mixed results—some surprisingly outperforming the moderate quota group. These results align with existing research: quota effectiveness depends heavily on implementation context, not just the numerical target.

Interactive version available here

Country-level analysis reveals important complexities. Spain, despite having ambitious gender parity goals, falls short of the directive’s requirements. Meanwhile, Portugal, Belgium, and the Netherlands approach the threshold despite setting a tilted target, while other countries in their respective categories lag significantly behind.

Countries without formal quotas may still promote board diversity through other mechanisms. The Nordic countries (Sweden, Denmark, and Finland) exemplify this approach—they near the directive’s targets likely due to strong institutional frameworks supporting gender equality, as noted by Mensi-Klarbach & Seierstad (2020).

Our findings emphasize the importance of context-specific analysis. Higher quota targets alone do not guarantee better outcomes—implementation context proves crucial. Additionally, some countries have very few listed companies (Bulgaria: 3, Latvia: 1 in 2024), raising questions about the directive’s practical impact in smaller markets. Many of these companies may not meet the size thresholds (EU Directive on company sizes) that trigger the directive’s requirements, highlighting the need to understand how corporate governance equality develops in different market contexts.

These results emphasize the need to understand the quotas in each context , as Mensi-Klarbach & Seierstad (2020) propose, and opens questions about the countries actually affected by the Directive. Here it was shown that a higher aim of the quota by itself does not show more effectiveness and thus it is necessary to examine the individual contexts. Moreover, there are some countries with just a handful of companies, like Bulgaria with 3 and Latvia with 1 in 2024. As mentioned before, the companies included here are not necessarily all the ones affected by the Directive, so it could be that the are countries that do not have large enough companies or have very few (EU Directive on company sizes). What happens in terms of equality in corporate governance in those contexts?

In any case, the Directive is meant to create a momentum and put in the agenda of the member states legislation in pro of gender equality on Corporate Boards. It is expected that each country adapts the legislation to their own contexts.

As a final remark, in January 2025 the Parliament sent letters of formal notice for failing to transpose the Directive to Belgium, Czechia, Estonia, Greece, Cyprus, Latvia, Luxembourg, Hungary, the Netherlands, Austria and Romania.

Methods and Data

The analysis uses European company data from BoardEx, which covers public companies and select private companies that disclose board composition publicly. (More on BoardEx data and processes.

We filtered the data to include only the 27 EU member states, focusing on companies with active ticker symbols that were not marked as de-listed. Our analysis includes only companies reporting 2024 data, tracking their board composition from their first appearance in the database.

Board composition calculations include all directors serving on any board (supervisory or executive) in each year. We calculated the percentage of women directors based on total board membership for each company and year.

Bibliography

Kirsch, A. (2021). Women on Board Policies in Member States and the Effects on Corporate Governance. Commissioned study from the Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs Directorate-General for Internal Policies. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/700556/IPOL_STU(2021)700556_EN.pdf

Mensi-Klarbach, H., & Seierstad, C. (2020). Gender Quotas on Corporate Boards: Similarities and Differences in Quota Scenarios. European Management Review, 17(3), 615–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12374

![[Upcoming paper] The dynamics of diversity on corporate boards](https://cbrc.sai.tugraz.at/wp-content/uploads/sites/42/2025/09/dynamica_diversity.png)